What makes an effective and fair EPR scheme?

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is an emerging trend across environmental policy in Europe. EPR involves extending producers’ economic and physical responsibility for their products to the post-consumer End-of-Life (EoL) stage. Its adaptability and potential to be implemented and cascaded across multiple product categories has been highlighted in recent years, making it an ideal candidate to address various problematic waste streams. This is certainly the case for France, who has a total of 15 EPR channels with only 5 being directly imposed by EU Directives.

Collaborating alongside BRE, Oakdene Hollins has recently been involved in building the evidence base for a proposed EPR for bulky waste and construction & demolition product categories for Defra. From this experience, Oakdene Hollins has pulled together 4 key considerations to help ensure the implementation of effective and fair EPR schemes:

1. Tackling environmental hotspots across the value chain, rather than those simply located at EoL

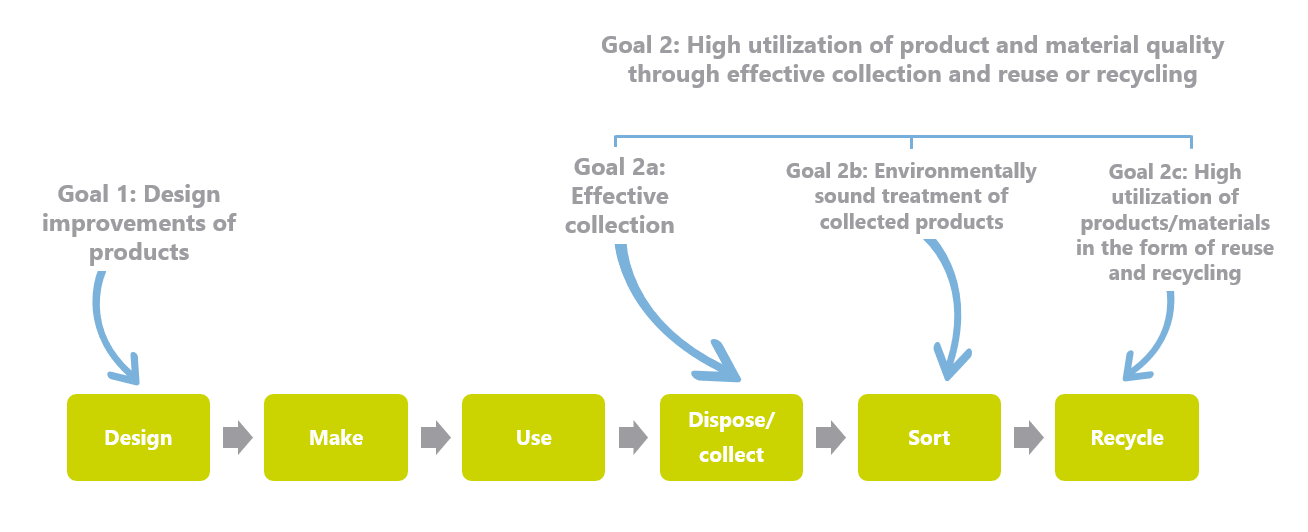

An environmental hotspot is a key area of environmental concern, and policy instruments should aim to tackle these. EPR has the potential to tackle environmental hotspots along the entire value chain, from encouraging design improvements to facilitating the correct disposal of products. The infographic below is based on the original OECD manual and highlights the two overarching environmentally related goals of an EPR. As you can see, Goal 1 focuses on the design stage of products, whilst Goal 2 (and its subsequent sub goals) focuses on tackling issues involved in the EoL stage.

In the scenario where the EoL collection and management of a product represents a significant environmental hotspot, a non-modulated EPR would not only transfer the financial burdens associated with EoL waste management from local authorities to producers, but also positively encourage activity up the waste hierarchy. A non-modulated EPR introduces a flat fee, based on full-net cost and the number of products placed on the market. Advanced Disposal Fee’s (ADFs) would be an effective tool in this circumstance, and retailers could play a role in communicating the purpose behind these additional fees to consumers.

Alternatively, in order to mitigate the non-EoL environmental hotspots, a modulated EPR (also known as eco-modulation) is required. The objective of eco-modulation is to differentiate between the sustainable and unsustainable products being placed on the market. Producers of sustainable products would pay a lower fee based on factors such as product durability, reparability, recyclability, recycled content and renewable/sustainable materials.

Although EPR is an effective instrument to positively encourage better EoL management (by transferring the full net cost to producers), it is clear that Defra’s ambitions for any future EPR scheme is to tackle environmental hotspots beyond this. Thus, it is important to consider the scope, aims and objectives of any scheme when deciding upon the most appropriate design features and mechanisms.

2. Market concentration and ease of implementation

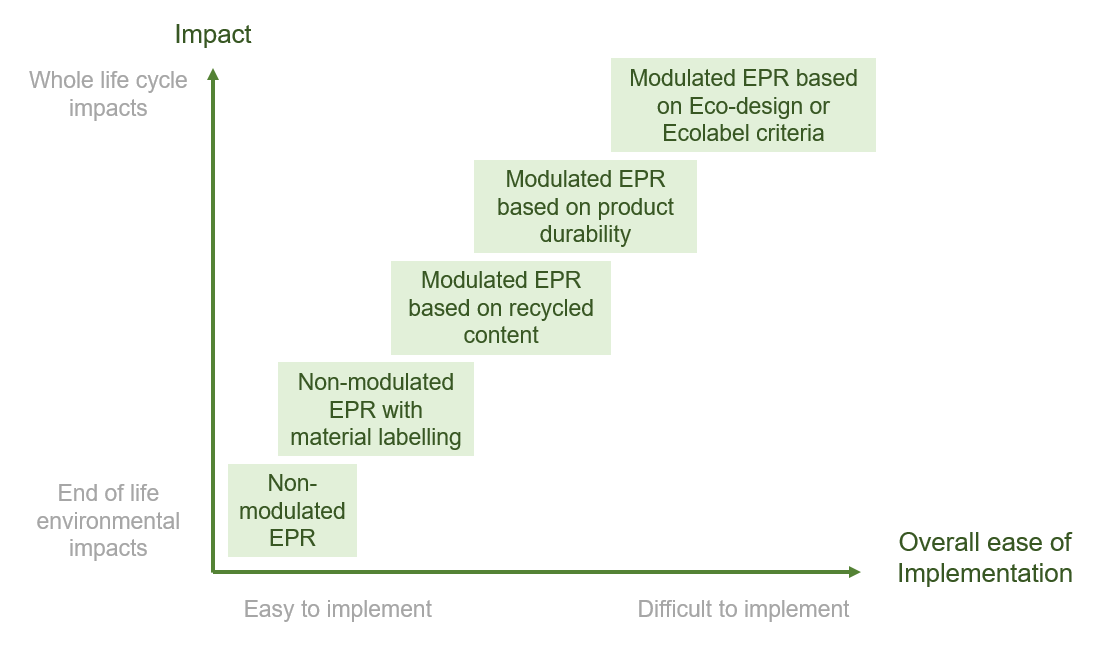

Whether an EPR is modulated or non-modulated is a very important factor which is determined by the scope of the aims as well an industry’s market concentration. If an industry has a high proportion of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), implementing a mandatory and modulated EPR may be overly burdensome.

In the scenario of a non-modulated EPR, from an administrative burden standpoint, the costs to businesses will be minimal since it can be calculated based on Placed On Market (POM) data (a system currently in place for packaging in the UK, i.e. the Packaging Recovery Note (PRN) scheme).

The overall ease of implementation would be more difficult for a modulated EPR since criteria for differentiating between environmentally good and bad products would need to be established and the means to which producers demonstrate conformance to these criteria would need to be determined. If a market is dominated by a few top manufacturers (i.e. a high concentration), it will experience less administrative burden for policy interventions such as EPR. These sectors will cope better with a modulated EPR.

The figure below is an example impact matrix for prioritising EPR features, highlighting the potential trade-off between tackling whole lifecycle impacts and overall ease of EPR implementation.

3. Must be backed up by a robust evidence base, especially in the situation where eco-modulation is introduced

To operate effectively and avoid any unintended consequences, schemes must be based on robust data. It is important to determine the quantities of the target product placed on the market, discarded at EoL, collected, recycled or otherwise treated. Many Member States have implemented EPR schemes in a phased approach to ensure a sufficient amount of robust environmental evidence was collected. For example, the French EPR for furniture was implemented in 3 separate stages:

A non-modulated EPR (focusing predominately on EoL collection and management) was initially established using producer fees to finance the scheme

Further environmental evidence (i.e. LCA’s) was gathered to reduce data gaps needed to establish eco-modulation upon

Eco-modulation was introduced a number of years after, offering a reduced levy to manufacturers who meet high environmental criteria (i.e. encouraging ecodesign)

4. Inclusion of R&D funding

As mentioned throughout this blog, it is clear that an EPR will effectively raise collection and recycling rates for targeted products and materials. However, such improvements may struggle to be sustained long term if there is no supporting increase in the demand for recycled products and availability of appropriate treatment capacity. This is where R&D funding can come into play.

R&D funding is vital to encourage the expansion of recycling technologies and capacity as well as transparent end markets for recoverable materials. These developments will heavily support the increased demands produced by any EPR. Both the UK and Scottish government are consulting over a potential EPR for mattresses. The lack of quality control and transparent end markets of recoverable materials has been highlighted as a high priority environmental hotspot for any future policy instrument to address. R&D funding would therefore help the mattress industry to determine more commercially attractive end markets.

There are growing discussions across Europe regarding the implementation of EPR to tackle problematic waste streams. In response to this, Oakdene Hollins has supported private organisations and trade associations to better understand the concept behind the environmental policy, as well as the various model types, design features and mechanisms it may employ. If you are interested in hearing more about EPR, please contact Olivia Judge (Olivia.Judge@oakdenehollins.com).